|

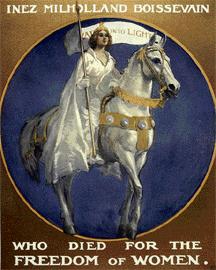

| March 3, 1913–Suffragist Parade. It was a Monday, the day before President Wilson's first inauguration. Photo: Library of Congress. |

It was on Monday, March 3, 1913.

The 1913 and 2013 parades were very different...

In 1913, It Became a Riot. Back then, the parade of women was huge for the time. The NY Times said 5,000 marchers; the National Park Service reported 8,000. It was the first major public demonstration in Washington. The 500,000 onlookers, mostly men, jeered the women as they went by. The parade devolved into a riot.

New Yorker Inez Milholland was on horseback at the front, and she pushed the edge of the crowd back with her horse. But behind her, push came to shove and the DC police couldn't keep order - some believe they didn't try. Secretary of War Stimson ordered cavalry in from Fort Myer to calm things down, but by the time the military arrived hundreds of women were injured. The marchers were protected by the First Amendment, but not by the police. The police superintendent was later cross-examined by Congress and was relieved of his job.

To be specific, a new breakaway sorority at Howard University, Delta Sigma Theta, demanded that it have a place in the parade. The Alpha Kappa Alpha sorority's leadership at Howard University had decided to break away from the socially ambitious club to form a new sorority that would be more socially activist.

These 22 Delta women wanted to march in the NAWSA parade. Alice Paul feared that participation by black women in still-segregated Washington would end the participation in the parade of the southern chapters of NAWSA and destroy NAWSA's unity.

Alice Paul was in charge of the "Congressional Committee" of NAWSA in 1912 after working for the British suffragettes. She started recruiting new people and raising money, much of it in New York City where NAWSA was then based. She tried to hold together the fragile coalition for a Federal Amendment for Votes for Women.

Inez Milholland disagreed on excluding the black sorority. She was the daughter of the first Treasurer of the NAACP, John E. Milholland, a Scotch-Irish Presbyterian who clung to the Lincoln Republican ethos of supporting equality among the races. She was adamant that the Deltas should be given their place, and allowed to march, in the parade lineup. She threatened to withdraw her commitment to lead the Washington parade on horseback. She had led the New York suffrage parade on horseback to great applause in New York City – it was a media attraction. She was also well connected with NAWSA supporters like Alva Belmont in New York City.

Alice Paul grudgingly agreed to allow the Howard University Deltas to join the parade. But she also had a plan, which appears not to have been shared with Inez Milholland, to minimize the danger to the parade by putting all the black women at the end of the parade, after the Men's League for Woman Suffrage.

It may be hard for some to appreciate how low the status of black women was in the Washington 100 years ago – or how threatened some white people were by signs of electoral activism. The outcome of the Civil War was to enfranchise black men. But the federal law was undermined by Jim Crow laws passed in southern states designed to suppress the black vote as well as the votes of some less-educated white men. For advocates of Votes for Women, seeing black women marching in a parade would remind southerners that adding women voters would double the number of potential black voters.

Contemporary accounts say that Alice Paul and the Congressional Committee leadership were worried that a visible black presence in the parade would set back progress toward a federal amendment. They may have foreseen that including black women in the parade would add to the potential for the violent reaction that actually occurred. Suffragist Mary Church Terrell reported that the Delta marchers were required to assemble in a segregated area. It was her opinion that:

If [Paul] and other white suffragist leaders could get the Anthony Amendment through without enfranchising African American women, they would do so.Linda Lumsden's biography of Inez Milholland makes clear that however much Inez may have gone along with excluding blacks in other social contexts, she was firm about the participation of the Deltas. Milholland was, like her father, a member of the NAACP. Citing Mary Church Terrell again, Lumsden says that Milholland insisted that the Howard contingent be allowed to march in the college section. Emmett Scott, secretary-treasurer of Howard University, said that Milholland

was unwilling to participate in a parade symbolizing a movement which was not big enough or broad enough to live up to the principles for which it was contending. (Lumsden, Inez, p. 91.)On the day of the parade, Ida B. Wells-Barnett, a former slave who had become a leading suffragist, defied the ruling of the Congressional Committee and marched with her Chicago NAWSA delegation. Others followed suit. In the end, 22 women marched in the Delta contingent and an unknown number of black NAWSA delegates marched with their geographical groups. But the only black organization to march as a group in the parade was the Howard delegation of Deltas! If 250 black women altogether were in the march – probably too high an estimate – and we use the lower NY Times estimate of the number of marchers, it means black marchers were at most 5 percent of the total.

|

| The Deltas listen to their leaders talk about the Deltas' mission, "public service" and "social activism." Photo by JT Marlin. |

For the 100th anniversary march, Delta Sigma Theta reported 20,000 marchers signed up to be in Washington for the parade. The National Park Service posted a crowd estimate of 20,000-25,000.

My estimate is that fewer than 1,000 of the marchers were white men and women. The racial percentages were therefore exactly reversed. In 1913, at most 5 percent of the marchers were black. In 2013, at most 5 percent were white.

Looking Forward, Not Back. Another major difference in 2013 is in the nature of the participation of the Deltas and the other women's groups.

- The traditional women's groups, mostly white women, were commemorating the actions of the suffragists to obtain the vote. They dressed up in the costumes of 1913 with purple, gold and white sashes and dresses. Although the picketing of the White House did not start until January 1917, the Turning Point Suffragist Memorial group had an effective tableau in place on March 2, 2013 showing the Silent Sentinels in front of the White House. When the demonstrators were arrested by the DC Police, Inez Milholland's sister Vida was one of those arrested, on July 4, 1917. They were taken away to the Occaquam workhouse in Lorton, Va., as described by a National Park Service Ranger who gave the history of woman suffrage in the United States while engaging the audience in some effective role playing (see second photo above).

- For the Deltas, the parade was less about history and pageantry and more about the next phase of the women's movement. Those Deltas marched with a purpose, every one of them dressed in their red and white colors, and the speeches in front of the Capitol (see bottom photo) were about moving on to new challenges, using their vote to attack continuing abuse of women in the home or in the workplace.

There was no rioting – far from it! It was an eerily quiet Sunday morning. The Deltas are all business. They didn't bring any marching bands, which explains why the crowds were thin. Since Washington, DC workers now mostly live in suburban Maryland and Virginia, there were few onlookers, maybe 5,000 at most. Protest marches in Washington are now a regular occurrence. The Deltas were in D.C. in January and will be back in a couple of months.

Inez Milholland's insistence that the Deltas be allowed to march took on more significance for me as I watched an hour-long parade of the sorority's many chapters go by. Inez knew which way the winds were blowing. For the Deltas in 2013:

- The purpose of most of the marchers, and the meaning of the event, was not so much a memorial to the achievements of yesterday.

- Rather, it was a reaffirmation of what the original marchers believed in. Progress has been achieved – that is obvious – since the first parade. But the Deltas marched not so much out of reverence for the past as out of determination to meet the challenges of today and tomorrow.

[I have written a longer post putting the two marches in a more complete historical context. I have long been fascinated by the story because Inez Milholland married my mother's uncle, Eugen Boissevain.]